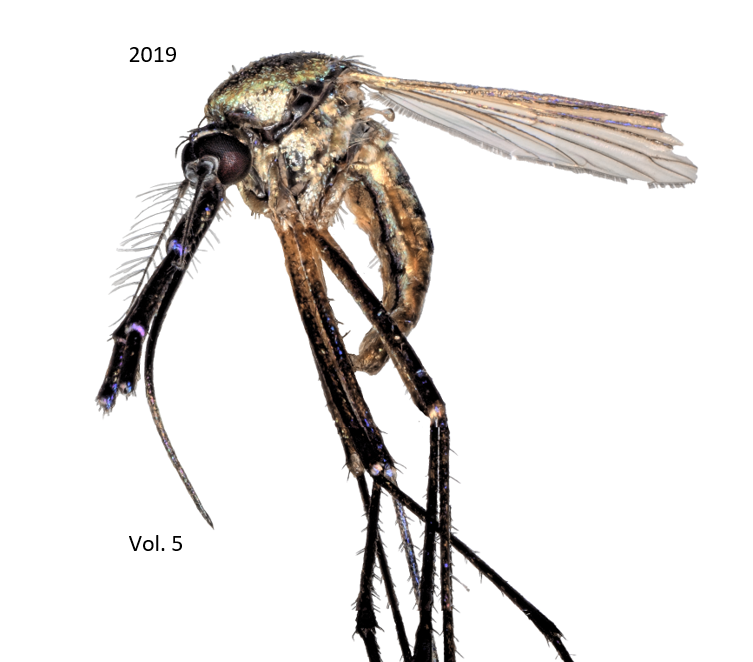

Foraging Behavior of Female Blow Flies (Diptera: Calliphoridae) Based on Visual Cues

Abstract

The attraction of blow flies to different resources can be affected by their ovarian development. For this study, the foraging behavior of the blow fly Calliphora terraenovae Macquart (Diptera: Calliphoridae) and attraction to visual cues mimicking flower colors were examined. Naïve blow flies that have not fed on protein and do not have eggs to lay should be attracted to flower colors that represent nectar resources, such as white, pink, yellow. Naïve male and female blow flies were put into experimental cages and exposed to seven flower water representing various colors for 24 h. After 24 h, the flies were removed and assorted by sex. Based on the results, both male and female flies preferred the color purple. Female flies preferred purple as well, but also showed preference for pink. By understanding the color preference of adult blow flies, forensic entomologists can further their understanding of attraction to various resources, whether for nutrients or as potential oviposition sites.

References

Brodie, B. S. 2015. Foraging and communication ecology of the common green bottle fly, Lucilia sericata (Meigen) (Diptera: Calliphoridae). PhD Dissertation, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC, Canada.

Browne, B. L. 2001. Quantitative aspects of the regulation of ovarian development in selected anautogenous Diptera: integration of endocrinology and nutrition. Entomol Exp Appl. 100: 137—149. onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1046/j.1570-7458.2001.00859.x/full

Byrd J.H, and J.L. Castner. 2010. Insects of forensic importance. In: J.H. Byrd and J.L. Castner (eds), Forensic entomology: the utility of arthropods in legal investigations. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

Dobson, H. 1994. Floral volatiles in insect biology In: E. Bernays (ed), Insect-Plant Interactions. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

Joseph, I., Mathew, D. G., Sathyan, P., and G. Vargheese. 2011. The use of insects in forensic investigations: An overview on the scope of forensic entomology. J Forensic Dent Sci 3: 89-91. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3296382/

R Core Team 2014. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing,Vienna, Austria. URL http://www.R-project.org/.

Sharma, R., Garg, R. K., and J.R. Guar. 2013. Various methods for the estimation of the post mortem interval from Calliphoridae: A review. Egypt J Forensic Sci 5: 1-12. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2090536X13000233

Williams, K. L., Browne, B. L., and A.C.M. Van Gerwen. 1979. Quantitative relationships between the ingestion of protein-rich material and ovarian development in the Australian sheep blowfly, Lucilia cuprina. Int J Inver Rep Dev. 1: 75—80. www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/01651269.1979.10553302

Wolff, M., Uribe, A., Ortiz, A., and P. Duque. 2001. A preliminary study of forensic entomology in Medellín, Colombia. Forensic Sci. Int. 120: 53-59. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11457610

Downloads

Published

Issue

Section

License

Instars supports the need for authors to share, disseminate and maximise the impact of their research. We take our responsibility as stewards of the online record seriously, and work to ensure our policies and procedures help to protect the integrity of scholarly works.

License to the Journal. The Author hereby licenses to the Journal the irrevocable, nonexclusive, and royalty-free rights as follows:

a. The Journal may publish the Article in any format, including electronic and print media. Specifically, this license include the right to reproduce, publicly distribute and display, and transmit the Article or portions thereof in any manner, through any medium now in existence or developed in the future, including but not limited to print, electronic, and digital media, computerized retrieval systems, and other formats

b. The Journal may prepare translations and abstracts and other similar adaptations of the Article in furtherance of its publication of the Article.

c. The Journal may use the Author's name, likeness, and institutional affiliation in connection with any use of the Article and in promoting the Article or the Journal.

d. The Journal may exercise these rights directly or by means of third parties. The Journal may authorize third-party publishers, aggregators, and printers to publish the Article or to include the Article in databases or other services. [Examples of such third parties include Westlaw, Lexis, and EBSCO.]

e. The Journal may without further permission from the Author transfer, assign, or sublicense the rights that the Journal has pursuant to the Agreement.

f. In order to foster wider access to the Article, especially for the benefit of the nonprofit community, the Author hereby grants to the Journal the authority to publish the Article with a Creative Commons "Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivatives" license. [The Author should consult the Creative Commons website (www.creativecommons.org) for further information]

g. This liscense of rights to the Journal shall take effect immediately. In the event that the Journal does not publish the Article, this license to the Journal shall temrinate upon written notification by the Journal to the Author, or upon termination of all publication by the Journal. To the extent that moral rights may apply to the Article, this agreement does not affect the moral rights of the Author in or to the Article.

Rights of the Author. Without suggesting any limit on other rights that the Author may h ave with respect to the Article, the Author retains the following rights. To the extent that the Journal holds similar rights with respect to the Article consistent with this Agreement, the Author shall hold these rights on a nonexclusive basis. To the extent that the Article includes edits and other contributions by the staff of the Journal, the rights of the Author in this Paragraph include the right to use such edits and contributions.

a. The Author may publish the Article in another scholarly journal, in a book, or by other means. The Author may exercise this right of publication only after the date of first publication of the ARticle in the Journal in any format.

b. The Author shall, without limitation, have the right to use the ARticle in any form or format in connection with the Author's teaching, conference presentations, lectures, other scholarly works, and for all of Author's academic and professional acitvities.

c. The Author shall at any time have the fright to make, or to authorize others to make, a preprint or a final published version of the ARticle available in digital form over the Internet, including, but not limited to, a website under the control fo the Author or the Author's employer or through digital repositories including, but not limited to, those maintained by scholarly societies, funding agencies, or the Author's employer. This right shall include, without limitation, the right of the Author to permit public access to the Article as part of a repository or through a service or domain maintained by teh Author's employing the institution or a service as required by law or by agreement with a funding agency. The Journal may in its discretion deposit the ARticle with any digital repository consisten with deposits permitted by the Author under ths paragraph. [Examples of such repositories include SSRN, arXiv.org, PubMed Central, and Academic Commons at Columbia University.]

d. Any of the foregoing permitted uses of the Article, or of a work based substantially on the Article, shall include an appropriate citation to the Article, stating that it has been or is to be published in the Journal, with name and date of the Journal publication and the Internet address for the website of the Journal.

Editing of the Article. This Agreement is subject to the understanding that the ordinary editing processes of the Journal will be diligently pursued and that the Article will not be published by the Journal unless, in tis final form, it is acceptable to the Author and the Journal.